The Small-Sword — the call of Honour?

Duelling, Anti-Duelling and the Masters of Fence

[Text of a lecture given at the 10th Smallsword Symposium in Edinburgh on 6th October, 2018. Please note that this is not a piece of original scholarly research, and was intended as an introduction to the topic for interested fencers. For deeper research on the subject I commend the reader to the bibliography appended to this paper.]

Honour! that guilded Idol of the Great;

For which, how do th' Ambitious toil and sweat,

And think't, with any Peril cheaply bought?

Hurry'd with Strong Desire, brook no Delay,

By what e'er Obstacles withstood;

But with impetuous Fury force their way,

And to the Gaudy Trifle wade thro' Seas of Blood.

So wrote Sir William “McGonagall” Hope in Chapter VI of his New, Short and Easy Method of Fencing (1707). It might be thought unusual that a fencing instructor would denigrate the concept of honour as a ‘gaudy trifle’ bought dearly with Peril and impetuous fury through a sanguinary ocean, particularly in a sword manual. After all, his main stock in trade, particularly at the turn of the eighteenth century, would surely be teaching the quality how to defend their honour in the duels which seemed, if the prurient reports in the news-letters and papers are to be believed, to be rife. In this paper I will take a (very brief!) look at the history of duelling, and the duels which raged over the meaning and purpose of this ritualised form of violence as played out between fencing masters, and social and political commentators.

Honour — history of the duel? The sixteenth century!

Historians such as Markku Peltonen and Roger Manning locate the popularisation of the ‘code Duello’ — a neologism derived from an archaic form of the Latin bellum, war — in the fashion for Italian books of courtly manners in the late Tudor period, particularly Baldassare Castiglione’s Libro del Cortegiano, The Book of the Courtier, originally written in 1528 and thereafter translated and published in 1561 by Thomas Hoby. Other books quickly followed on a similar theme, stressing that a nobleman’s a nobleman’s honour was based on his (perceived) integrity, his civility and his courtesie, and to cast doubt on that — that is, to give the lie — struck at the very root of a man’s status, and was to be resented and defended at all costs — with one’s life if necessary. In the wake of the popularity of Castiglione and the Italian ideal of ‘courtliness’, as well as frequent trade between England and the continent, rapiers became fashionable — and of course Italian tutors, following the money, were soon to be found in England teaching their national weapon. Most famous of these perhaps (and certainly most important for our purposes here today) was Vincentio Saviolo, who not only taught and published on rapier fencing specifically, but laid out in excruciating detail in the second part of his fencing treatise how a nobleman was to go about resenting the ‘lie’, the intricate specifics of issuing and answering a challenge, and so on. Resenting “the Lie” and issuing challenges was such an important part of the way of the Rapier, Silver complains of one Signor Rocco Bonetti’s rapier school that

“...he had in his school a large square table, with a green carpet, done round with a very broad rich fringe of gold, always standing upon it a very fair Standish covered with crimson velvet, with ink, pens, pen-dust, and sealing wax, and quivers of very excellent fine paper gilded, ready for the noblemen & gentlemen (upon occasion) to write their letters, being then desirous to follow their fight, to send their men to dispatch their business.”

Silver of course himself challenged Vincento and his brother Jieronimo, but these two not answering his challenge, he, his brother Toby, and other Maisters just happened to find themselves innocently ‘drinking of bottled ale hard by Vincentio's school, in a hall where the Italians must of necessity pass through to go to their school’ and a fight ensued where they had to be parted. Soon enough however the Italians put out the word that they had ‘beaten all the masters of defence in London, who set upon them in a house together... [which] won the Italian fencers their credit again.’ Bonetti himself was killed by the swordsman Austin Bagger in 1587, who, after wounding him in his heels, breech and feet, then “trode upon him”, in utter contempt of those courtly rules so in vogue. Though the English Maisters rail particularly against the ineffective fight of the Italian rapier, and the foolishness of their schools of courtliness which taught wielding a quill as well as they did a sword, one must also bear in mind that they were fighting a pamphlet war to protect their own guild and financial interests with the monopoly granted to them by Henry VIII.

Much of the debate on the legitimacy of duelling mirrored the seventeenth-eighteenth century ‘Quarrel of the ‘Ancients and the Moderns’ which raged in poetics. For the critics, the question was whether the ancient Greeks and Romans had reached perfection in culture which could only be imperfectly emulated, or, whether this was in fact not the case, and the innovations and inventions of the Renaissance and Enlightenment showed that mankind was ever progressing. This would come, in the eighteenth century, to be an essentially Tory/Whig split in the interpretation of history - indeed, we can still see some of its remnants in martial arts discussions, with Classical and Sport fencers alleging that theirs is the pinnacle of evolution of fencing, and HEMA-ists arguing that theirs is a degenerate form of the true historical art of the sword. For theorists of the duel, the important question in proving its legitimacy or otherwise was whether the duel’s origins had its wellspring in ancient Classical — and therefore hallowed, and perfect — ritual, or was instead a despicably fashionable and above all modern import from those debauched Romans, the French and Italians. A related concern was whether the duel was a foreign import or a domestic tradition, a relic of medieval chivalric ideals or modern foppery. The antiquary John Selden, subtitled his 1610 Duello “or single combat from antiquitie deriued into this kingdome of England” and argued that it had come from the Normans who “were the first authors of it in this their conquered kingdome”. Silver understood the duel to be a modern, foreign, dangerous fad:

“Fencing (Right honorable) in this new fangled age, is like our fashions, every day a change, resembling the chameleon, who alters himself into all colors save white. So fencing changes into all wards save the right. [...] The reason which moved me to adventure so great a task [as writing my Paradoxes of Defence], is the desire I have to bring the truth to light, which has a long time lain hidden in the cave of contempt, while we like degenerate sons, have forsaken our forefathers virtues with their weapons, and have lusted like men sick of a strange ague, after the strange vices and devices of Italian, French, and Spanish fencers, little remembering, that these apish toys could not free Rome from Brennius's sack, nor France from the King Henry the Fifth his conquest. [...] perceiving the great abuses of the Italian Teachers of Offense done unto them, and great errors, inconveniences, & false resolutions they have brought them into, has informed me, even for pity of their most lamentable wounds and slaughters, & as I verily think it my bound duty, with all love and humility to admonish them to take heed, how they submit themselves into the hand of Italian teachers of defence [...] and to beware how they forsake or suspect their own natural fight, that they may by casting off these Italianated, weak, fantastical, and most devilish and imperfect fights, and by exercising their own ancient weapons, be restored, or achieve unto the natural, and most manly and victorious fight again.”

James VI and I declared that duelling ‘was first borne and bred in Forraine parts; but after convaied over to this Island’, and in 1613 following a particularly violent duel he issued proclamations prohibiting publishing reports of duels, and then proclamations against private challenges, though these seem not to have done a great deal to abate the tide. Subsequent regimes throughout the seventeenth century brought regular anti-duelling bills which either failed to pass in parliament, or had little practical effect.

Another obvious flaw in this courtly ideal of ‘politeness’ proposed by Castiglione and gleefully accepted by the noblesse was that one might then perpetrate all manner of villainy, so long as one did so politely, and under no circumstances accused another of lying. Saviolo, indeed, goes into great detail about the various sorts of lies which could be given, their degree of insult, and how they should be answered, asserting that “modesty and courtesy are most convenient ornaments whereby men shall avoid many dangers and quarrels.” This contradiction did not go unnoticed at the time — Shakespeare has his Hamlet say:

That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain—

At least I am sure it may be so in Denmark.

(Note the implication that such false-seeming is a particularly continental vice). Lady Macbeth exhorts her husband to “look like the innocent flower/But be the serpent under it”. As the cult and culture of courtliness persisted into the eighteenth century, this concern did not abate. It was argued by duelling’s proponents that the usual requirement for issuing a challenge and meeting at a neutral ground took the fight away from the immediate point of the quarrel and the passions it had provoked. Also, the possibility of death at swordpoint (and, later, pistol) was supposed to ensure that courtesy was the norm — an armed society being, allegedly, a polite society. This point was reiterated in 1714 by Bernard Mandeville in The Fable of the Bees:

Those that rail at duelling do not consider the benefit the society receives from that fashion; if every ill-bred fellow might use what language he pleased without being called to an account for it, all conversation would be spoiled. Some grave people tell us that the Greeks and Romans were such valiant men, and yet knew nothing of duelling but in their country's quarrel. This is very true, but for that reason the kings and princes in Homer gave one another worse language than our porters and hackney coachmen would be able to bear without resentment.

Would you hinder duelling, pardon nobody that offends that way, and make the laws as severe as you can, but do not take away the thing itself, the custom of it. This will not only prevent the frequency of it, but likewise, by rendering the most resolute and most powerful cautious and circumspect in their behaviour, polish and brighten society in general. Nothing civilizes a man equally as his fear, and if not all (as my lord Rochester said), at least most men would be cowards if they durst. The dread of being called to an account keeps abundance in awe; and there are thousands of mannerly and well-accomplished gentlemen in Europe who would have been insolent and insupportable coxcombs without it...

In reality, it seems to have armed fragile masculinity, and even though the requisite pause between the offence happening, the challenge being issued and the fight itself occurring was meant to ensure a distinction between the duel proper and a bar brawl, perhaps because one has attempted to accost the lead singer of UB40, fatal fights continued to happen for the most trivial and petty of reasons. In the Spectator of Saturday June 23 1711, “Isaac Bickerstaff” wrote:

The great Violation of the Point of Honour from Man to Man, is giving the Lie. One may tell another he Whores, Drinks, Blasphemes, and it may pass unresented; but to say he Lies, tho' but in Jest, is an Affront that nothing but Blood can expiate. The Reason perhaps may be, because no other Vice implies a want of Courage so much as the making of a Lie; and therefore telling a man he Lies, is touching him in the most sensible Part of Honour, and indirectly calling him a Coward...The placing the Point of Honour in this false kind of Courage, has given Occasion to the very Refuse of Mankind, who have neither Virtue nor common Sense, to set up for Men of Honour...Death is not sufficient to deter Men who make it their Glory to despise it, but if every one that fought a Duel were to stand in the Pillory, it would quickly lessen the Number of these imaginary Men of Honour, and put an end to so absurd a Practice....When Honour is a Support to virtuous Principles, and runs parallel with the Laws of God and our Country, it cannot be too much cherished and encouraged: But when the Dictates of Honour are contrary to those of Religion and Equity, they are the greatest Depravations of human Nature, by giving wrong Ambitions and false Ideas of what is good and laudable; and should therefore be exploded by all Governments, and driven out as the Bane and Plague of Human Society.

“Isaac Bickerstaff” was in fact the Irish writer Sir Richard Steele. A British Army Guards’ ensign, he attracted notoriety in June 1700 by fighting a duel with another Irishman in Hyde Park and almost killing his opponent, probably an officer of the Queen's regiment of dragoons named Henry Kelly. Publishing moralistic writings such as the 1701 The Christian Hero, which attempted to point out the differences between perceived and actual masculinity, and his subsequent writings in the Tatler and Spectator (as above) left him open to condemnation as an hypocrite, as his own life was seen to be less than exemplary. In his plays and essays, Steele became one of the most vocal critics of duelling. “Bickerstaff” in Tatler 93 mocks fencing masters who are incensed by his stance:

I had several Hints and Advertisements from unknown Hands, that some, who are Enemies to my Labours, design to demand the fashionable Way of Satisfaction for the Disturbance my Lucubrations have given them…My latest Treatises against Duels have so far disobliged the Fraternity of the noble Science of Defence, that I can get none of them to shew me so much as one Pass. I am therefore obliged to learn by Book, and have accordingly several Volumes, wherein all the Postures are exactly delineated… I have upon my Chamber-Walls, drawn at full Length, the Figures of all Sorts of Men, from eight Foot to three Foot two Inches. Within this Height, I take it, that all the fighting Men of Great Britain are comprehended… I must confess, I have had great Success this Morning, and have hit every Figure round the Room in a mortal Part, without receiving the least Hurt, except a little Scratch by falling on my Face, in pushing at one at the lower End of my Chamber; but I recovered so quick, and jumped so nimble into my Guard, that if he had been alive, he could not have hurt me.

Some of you might indeed have recognised the name Isaac Bickerstaff as the addressee of a published open ‘letter’ written by the Edinburgh fencing master William Machrie “Professor of Both-swords” in 1711. This letter is in direct response to Steele/Bickerstaff’s anti-duelling essays. He begins:

Sir,

When you were a Tatler, I read over all your Lucubrations, and since you turn'd Spectator, I have done the same; ... I would not have given myself the Trouble of putting Pen to Paper against you, had you not in one of your Tatlers ridicul'd Duelling, which I shall defend...

Tatler and Spectator were the ‘Bickerstaff’ publications — which had also been subtitled ‘The Lucubrations of Isaac Bickerstaff esq.’ Machrie continues:

...Where we have not given up our Liberties, we are in full Power to exercise those reserv'd to us; but no Man hath given any Liberty to any Magistrate whatsoever, by Statutes, to take away the Power of Defending his Life, Honour and Property, except upon better condition that he make suitable provision to protect him in all these, by the Sword of Justice. Therefore all Laws against Repairing Men's Honour by Duelling, are unjust, and of themselves Null, untill States and Soverigns provide for its Reparation, by erecting Courts of Honour.

...From the Law of Nations, It is objected, that all Societies and States have under great Penalties, discharged Duelling, as an Incroachment upon the Prerogative Royal.

My Answer is, that the most part of the World are in an Error, from which nothing can be concluded to Constitute a Law, s[ee]ing all Laws and Customs must be Reasonable.

...But now I imagine, I hear you saying ne sutor ultra Crepidam, what have Fencing Masters to do with Learn'd Dissertation.

I Answer very clearly, as much as a Disbanded Captain, a Rake and a Debauchee hath to Assume the Title and Power of a Censor, nay more, since these Thirty Years, I but Fenced one half of the Day, and Studied the other half, which you never had time to do, for Whoring and Drinking. I am.

Sir,

Your Humble Servant

Will Machrie

Machrie shifts the terms of the debate, not to be a straight discussion of the rights and wrongs of duelling in and of itself, instead stressing the principle of self-defence: “If any Man attacks me, I know not what length he may go, he hath thereby declared himself mine Enemy, by which it is but naturally allowable for me to commit Hostilities upon him.” He also appeals directly to both Classical and Biblical precedent, alleging particularly that “the Goths and Vandals allowed of it in their Law, from whom we in Scotland borrowed it.” He also notes Steele’s hypocrisy, as a duellist himself : “Noblemen and Gentlemen when affronted, always Fight single Combats: And you Mr Bickerstaff, tho' in your Tatler you Ridicul'd Duels, was very ready when ever your Honour was attack'd, to fight a Single Combat with your Offenders, and had others to stand Friends and Abetters.”

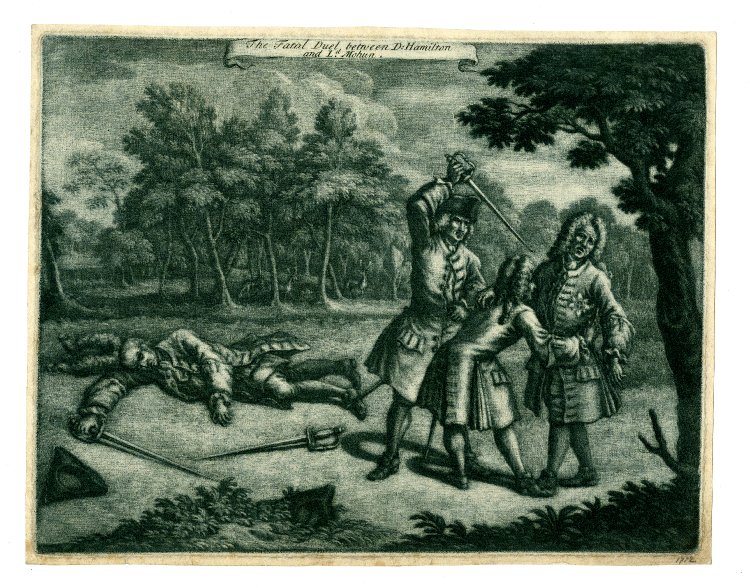

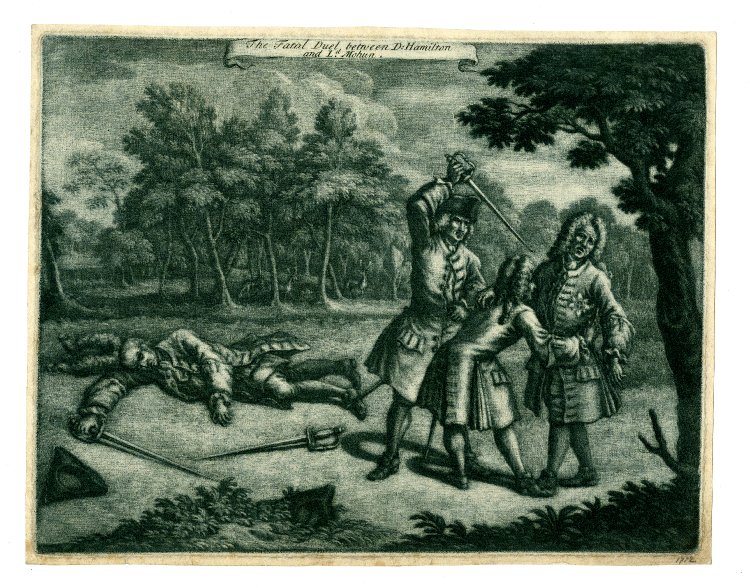

Machrie’s ‘Bickerstaff’ letter was written only a year before one of the most infamous duels of the early eighteenth century. The duel between Hamilton (no, not that one) and Lord Mohun of November 1712 was widely reported in the newsletters and newspapers, both because of the notoriety of the parties and because of the political overtones of the fight. Lord Mohun’s father had been killed in a duel, and he himself had fought his first duel aged 15, leading a dissolute life peppered with violent incidents — including several duels during which he killed three men, and an attempted kidnapping which went badly wrong — for all of which he escaped punishment, probably due to his aristocratic status. He was also a committed Whig. The Duke of Hamilton was a leading Scottish Tory politician, and had recently been appointed Ambassador to France. The initial impetus of the duel was a long-running legal dispute over Mohun’s inheritance of the estate of the earl of Macclesfield, uncle of his former wife, for which Hamilton was a rival claimant. A report at the time noted that “[i]t is to be remembered, that the Lord Mohun was the Person who gave the Affront, which the Duke, observing him to be in Drink, disdain’d to regard”. But the two being so prominent in their respective parliamentary groupings, it was soon whipped up into as much a factional dispute as a legal one, the Tories painting it as a Whig plot designed to derail the prospective peace agreement with France. The press and public went wild — indeed, one can find the sort of ‘desperate marketing’ in the classified ads tying into the events, such as this reprint of Selden explicitly marketed relating to the duel, just beside an advert for playing cards.

The fact that both parties’ seconds joined in the fight, both duellists were killed, and the further allegation that Mohun’s second, General George MacCartney, had in fact delivered the fatal thrust on Hamilton (who might otherwise have survived) and afterwards fled, only heightened the interest in the wretched affair. It was reported in a level of detail highly unusual for the time — the interested historian or martial artist searching through the Burney newspaper collection for duels is usually starved of much information save that a particular duel had occurred; not even the weapons chosen are often reported. The Post Boy of November 22nd gave some detailed recollections of the manoeuvres of the seconds:

They all drew immediately, and Mackartney made a full Pass at Hamilton, which he parrying down with great force, wounded himself in his Instep; however, he took that Opportunity to close with and disarm Mackartney; which being done, he turn’d his Head, and seeing my Lord Mohun fall, and the Duke upon him, he ran to the Duke’s Assistance; and that he might with the more Ease help him, he flung down both the Swords; and as he was raising my Lord Duke up, he says, That he saw Mackartney make a Push at his Grace; that he immediately look’d to see if he had wounded him; but seeing no Blood, he took up his sword, expecting Mackartney would attack him again; but he walk’d off… My Lord Duke’s Steward… opening his Grace’s Breast, soon discover’d a Wound on the Left Side, which came in between the Left Shoulder and Pap, and went slantingly down through the Midriff into his Belly: This wound is thought impracticable for my Lord Mohun to give him.

Lord Mohun lying mortally wounded on ground to left; his second, George MacCartney, centre, sword raised for fatal blow to the Duke of Hamilton. The duel was fought on 12 November 1712.

December 13th’s edition of the Post Boy gave a pruriently exact account of the various wounds of the late combatants:

Henry Amy, a Surgeon, depos’d, That he found Duke Hamilton had receive’d a Wound by a Push, which had cut the Artery and small Tendon of his Right Arm; another in his Right Leg, 8 Inches long, which he suppos’d to be by a Slash, it being very large; another small one in his Left Leg, near the Instep; and a fourth on his Left Side, between the second and third Rib, which ran down into his Body, most forwards, having pierc’d the Skirt of his Midriff, and gone thro’ his Caul. That the Wound in his Arm caus’d his so speedy Death, thro’ Loss of Blood by the Artery; and, That he might have liv’d two or three Days with the Wound in his Breast; which Wound cou’d not be given but by a Thrust coming from an Arm that reach’d over or was above him. He farther depos’d, That he also view’d the Lord Mohun’s Body, and found that he had a Wound between his short Ribs, quite through his Belly; another about 3 Inches deep, in the upper part of his Thigh; a large Wound, about 4 Inches wide, in his Groin, a little higher, which was the Cause of his immediate Death; and another small Wound on his Left Side; and, That the Fingers of his Left Hand were cut.

Clearly Lord Mohun was using his left hand to help defend himself; Sir William Hope would only partially have approved, for though he says in his New Method that “the dextrous use of the left hand is of such use [...] that I cannot enof recommend it” — he also strongly advocates the wearing of a stout leather gauntlet up to the elbow. Lord Mohun appears from this surgeon’s report not to have bothered. The Miscellany of popular antiquities sums up the duel thus:

[...] the truth of the matter seems to be that both sets of antagonists, principals as well as seconds, were so transported by the virulence of personal enmity as to neglect all the laws both of the gladiatorial art and the duelling code, and engage each other with the fury of wild beasts.

The report in The Post Boy November 18 1712 has further eyewitness accounts:

…the Spectators of the Duel were examin’d, and we hear, that my Lord Duke and the Lord Mohun did not parry, but gave Thrusts at each other; and the latter shortening his sword, stabbed the Duke in the upper part of his Left Breast, running downwards into his Body, (which Wound, upon probing, was about 14 Inches long) who expired soon after he was put into the Coach.

These descriptions chime with Sir William Hope’s complaints about lack of defensive action in French common-method fencing, in his New Method of 1707. In Chapter VI, he writes of just the sort of fencers and fencing which would be seen in the Hamilton-Mohun duel:

And I cannot but in this place take notice, how inconsistent the above mentioned Monsieur de Liancour is with himself, when he is giving directions anent a man's behaviour against this rash, and precipitantly forward temper, which alwise advances. For there...he advises a man to thrust for the most part, alwise out at a venture, upon such an adversary's pursuit, without so much as ever offering first to go to the sword, or to parie; which is a very strange advice for so great a master, and much the same as if he should have said,

“Whenever any man pursues you violently and irregularly, abandon quite your art, and relying meerly upon chance, thrust smartly out upon him;”

which is a ventorious, and I may say, so foolhardy a practice, that notwithstanding of its sometimes succeeding, I altogether condemn in any artist, unless, as I have said elsewhere, [...] he be driven beyond the bounds and limits of all art, so that it can be no more serviceable to him, which is what can scarecely fall out: And if Monsieur de Liancour had confined this direction of alwise thrusting out, only to this difficult juncture I have named, then I shoud willingly have agreed with him. But seeing he makes this thrusting out (and which is indeed a kind of thrusting upon time) his chief, and I may say only, contrary to this forward and rambling temper, I cannot but dissent from him by disapproving of it.

Hope’s great innovation in the New Method was of course the use of the hanging guard in Seconde, of which which he says “THE Defensive part of the Art of the Sword, or Parade, being most difficult, and the Pursuit or Offensive Part most easie; the keeping this Guard, quite renverses that, by rendering the Defensive Part more easie, and the Offensive more difficult: Which New and extraordinary Alteration, is no small advantage to the Art.” Using the New Method, it would be easier to parry a thrust, and then under cover of the true or great cross, come to grapple with and disarm one’s opponent, thereby offering him ‘a fair opportunity, both as a man of honour, of defending himself, and as a good Christian, of saving his adversary (Honour, as well as religion, obliging him to both’) – though Hope is clear that, should an opponent in that position struggle, he is to be run through

“for, if I must either lose my own or take my Adversary’s Life, I can never be condemned, for choosing of two Evils the least. Necessity hath neither Law nor Gospel against it.

In the New Method Hope advances a similar argument to Machrie’s, which was to be developed further still in his 1724 Vindication of the True Art of Self-Defence, that of the difference between fencing and duelling. To fence is not necessarily to duel, and those who wish to ban the former as well as the latter in Hope’s mind are guilty of attempting to cut out healthy tissue with the diseased.

There is a vast difference betwixt Assaulting in a School with blunts for a man’s diversion, and engaging in the Fields with Sharps for a man’s Life. And whatever latitude a man may take in the one, to show his address and dexterity, yet he ought to go a little more warily and securely to work when he is concerned in the other. For in Assaulting with Fleurets, a man may venture upon many difficult and nice Lessons, wherein if he fail, he runs no great risqué… But with Sharps, the more plain and simple his Lessons of pursuit are, the more secure is his Person… A man may indeed, in School-play, recover a mistimed thrust. But here, a great escape being once made, is irrecoverable.

A clear distinction is drawn between ‘the pleasure of assaulting in schools’, where lives are not at risk and all manner of intricate play may be attempted, and a duel with sharps. Where masters fail to recognise or admit to such a distinction, lives are put at risk.

Hope condemns duelling – though Honour is clearly an important part of a Gentleman’s life, he refers to the quarrels which lead to duels in disparaging terms, as trifles, or drunken scuffles, not worth the sacrifice of lives, and indeed the history of duelling is stuffed with those who have fought over incredibly trivial matters. I will give two local examples here (though admittedly, at the wrong end of the century, and most likely done with pistols), “[i]n 1790, at a ball in Edinburgh, Mr MacDonnell felt that Mr MacLeod had looked at him the wrong way, leading to an argument during which MacDonnell hit MacLeod with his cane... and led to a duel in which MacLeod was killed...” — it might here be noted that in Saviolo’s Honourable Quarrels he mentions the danger of ‘looking insolently’ at a gentleman — “... in 1797 Mr Anderson and Mr Barker fought a duel in Leith after Barker, a brewer, made sarcastic comments concerning the rules that Anderson had drafted outlining the running of the Leith Assembly rooms.”[1] Considered in this light it is perhaps not as surprising as it might otherwise be that in his Vindication, Hope leans heavily on Dr John Cockburn’s anti-duelling tract, The history and examination of duels. : Shewing their heinous nature and the necessity of suppressing them (1720) which is quoted and paraphrased a great deal throughout the Vindication — it’s almost a Cockburn fanfic. Hope opens by noting that

Duelling, or Single Combats, either without, or with Seconds, are of such bad Consequence, and have destroy’d within these Hundred Years, so many Brave Men, that I am persuaded, there is no Man of True Honour, but will be well satisfied with my reducing into so small a Bounds as the following Vindication, the chief Arguments against them.

There are none but the Vindictive and Revengful, who can have any Pleasure or Satisfaction in them; and seeing, that by so much as they possess of this Unchristian Temper, by so much do they Ungentleman themselves, I shall have the less Regard for them.

They are then only the True Gentlemen, and consequently the Honourable, whose Judgment I shall respect in this Matter; if they but approve of it, I am satisfied, and shall very easily digest the indifferent Opinion any other less deserving Persons may have of it.

Any Person of ordinary Sense and Ingenuity, altho’ neither Gentleman nor Scholar, will be capable to understand the Strength of the Arguments adduced, against the Giving and Answering of Challenges; and, if he be a good Christian, he will do it the better, and the more readily enter into the Design of the Book, which is chiefly to save Men’s Lives.

Hope returns to the idea of “ungentlemanning’ oneself later in the Vindication, where he sends the point further home by declaring that ‘cowards among sword-men are like eunuchs among men’. It is clear that Hope emphatically does not equate not fighting duels with a cowardly temper – in his formulation of a Christian honour, a man ungentlemans himself by his unchristianness in the fight. Unlike other Christian anti-duellists however, who would have fencing outlawed, and enjoin their readers to often too-high ideals, Hope acknowledges the fallenness of this world, writing:

Seeing the present State of the World, at least with us, is thus corrupt, therefore he who cannot live as a Recluse, but resolves to set out into the World, and to engage into the Affairs of it, either generously to serve the Publick, or lawfully and innocently serve himself, I say “This Man may conclude to meet with Injuries, Provocations, and what is called Affronts, and should prepare for them, even as they who intend a voyage do wisely provide against Storms, Tempests and rough Weather, to which the Sea is liable, as everyone knows.”

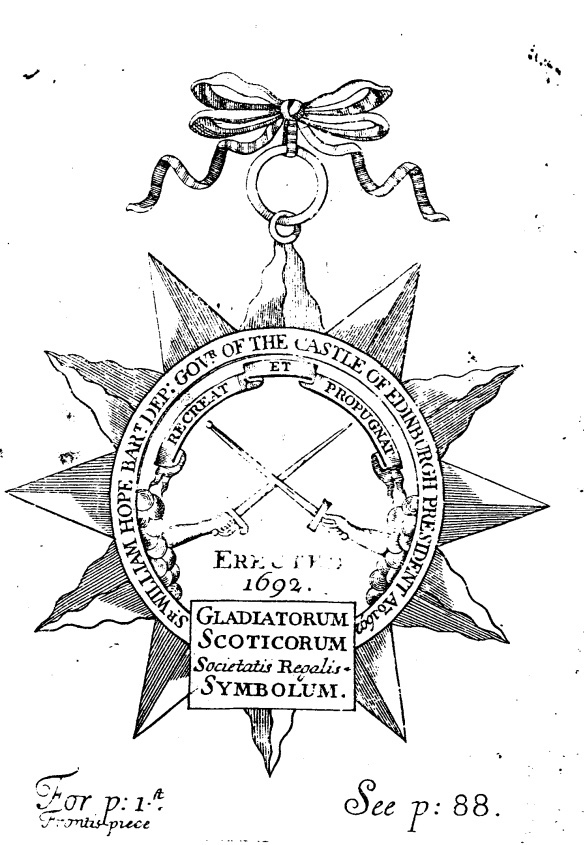

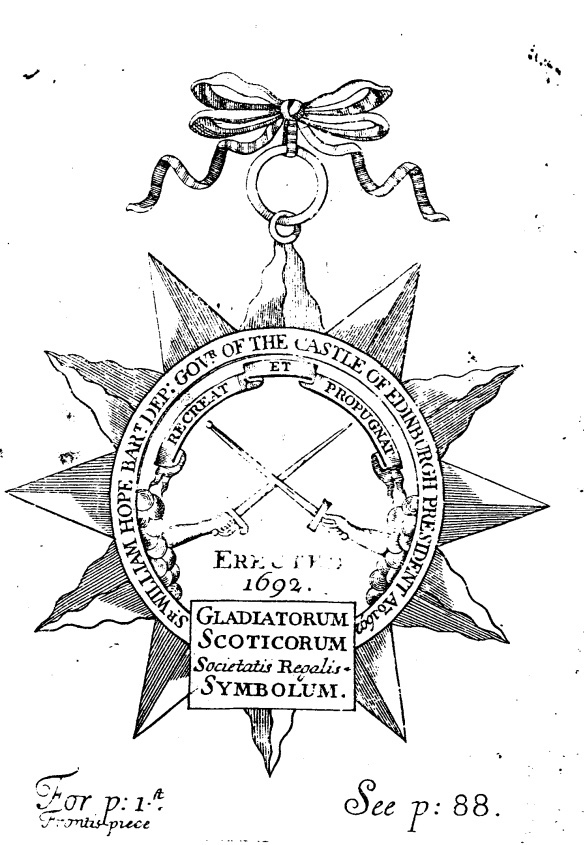

Hope, unsurprisingly, advocates learning fencing in the true sense of the word, that is, for defence rather than offence, particularly against what he terms “a surprise attacque with sharps”, as does Machrie in his letter to Bickerstaff. More surprisingly, Doctor Cockburn would appear to agree with him, acknowledging “the Principle of Self-Defence both reasonable and necessary; and that it is both a natural and religious Duty, to keep our selves from Contempt and Injury.” Hope’s solution is one that had been mooted in preceding centuries, most notably by the philosopher and statesman, Francis Bacon — a court of Honour (also mentioned by Machrie). Hope says that he has been involved in attempts to erect such a court since 1692 (around the time of the Sword-Man’s Vade Mecum and Compleat Fencing-Master). It was to have had a two-fold purpose — to be a regulatory body with a tight hold on who was to be allowed to teach fencing, “and particularly, with full Power to them, to Prevent if possible, Cognosce upon, and Determine all Differences betwixt Parties, upon giving Satisfaction, and other Points of Honour, whom they are hereby empowered to call before them, for the more effectual preventing of Duels.”

Hope’s crest for the Society of Swordsmen of Scotland

Neither Hope’s nor Bacon’s honour court came to pass in quite the way they imagined it. Though, it is surely no coincidence that strict English defamation laws began around the time James VI/I first attempted to outlaw duelling. Shifting public opinion tends to be a marathon rather than a sprint, and duelling continued to be both horrifying and fascinating to the public, though the practice shifted from swords to pistols through the decades after Hope’s Vindication. The concept of manliness, and indeed gentlemanliness in particular came to be questioned — should a gentleman be so wedded to worldly honour that he risk his life and his soul to redress a perceived slight? More and more, opponents of duelling culture stressed its alienness to British life, as the Rev. John Bennett preached from the pulpit of St Mary’s Church, Manchester in 1783:

“I believe the prevalence of Duelling, in this kingdom, is considerable, owing to our fondness for even the fopperies and vices of our neighbours on the continent [...] France, indeed hath of late been a fruitful and convenient nursery of almost every fashionable absurdity which distinguishes our manners; and threatens to annihilate those sterling virtues, which once, characterized the English [...] and till Britain hath given up this ridiculous taste for the customs and maxims of so frivolous a nation; her sun, I am persuaded, will gradually be setting, and her empire drawing to a close.”

A discourse against the fatal practice of duelling; occasioned by a late melancholy event, And preached at St. Mary's Church, in Manchester, On Sunday the 23d of March, 1783. By the Rev. John Bennett, pp.8-10

Duelling with swords certainly dropped off sharply after the 1720s-30s, when swords ceased to be carried as a matter of course and fencing came gradually to be seen as a diverting recreational activity ‘giving additional strength of body, proper confidence, grace, activity, and address’, with the defensive part a distinct secondary focus. Violent behaviour came increasingly to be condemned in public life as not a “gentlemanly” thing, and the pistol took over as the main weapon of choice for duels, pistol duelling looked on as seemingly calmer and less actively violent than a sword fight. Captain John Godfrey, in his 1747 A Treatise upon the Useful Science of Defence, discourses on differences in temperament in discussing the different uses of the back- and the small-sword:

[...] I must take notice of the Superiority the Back-Sword has over the Small, in point of Use. Indeed as we cannot put a Stop to the natural Passions of Mankind, which, according to their Constitution and Temperament, more or less excite them to Mischief, if not proportionably checked by Reason; we must endeavour at the readiest Means of putting it out of their Power to do us that MIschief their Passions prompt them to. It is therefore requisite to learn the Small-Sword, in order to guard against the Attempts of that Man, with whose brutal Ferocity no Reason will prevail: But then that Necessity is productive of Pain and Misery, though it tends to the Preservation of your Life. Killing a Man, when you are forced upon the Defensive, clears you in human Laws; but how far you are justified in Christianity, the Gospel best can tell you... But Laws divine as well as human justify and protect you in your Country’s Cause. Sure the wide Difference between killing Numbers of your Enemy in Battle, and one Man in a Quarrel, ever so much in your own Defence, every calm thinking Man cannot but allow.

It is therefore that the Small-Sword, in point of true Reason, is not necessary; it is only a subservient Instrument to our Passions. This is viewing it in the tenderest Light; but I fear it oftener proves, proportionably to it’s Practice, an Incentive and Encouragement to Mischief.

But the Back-Sword, sure, must be distinguished from the other, because it is as necessary in the Army, as the other is mischievous in Quarrels, and deadly in Duels. The Small-Sword is the Call of Honour, the Back-Sword the Call of Duty. I wish Honour had more Acquaintance with Honesty than it generally has....It need not be said I here discourage the Small-Sword, I only oppose it’s Abuse... I am not that Saint to advise a Man to let another pull him by the Nose; but then I would have him to be the brave User of his Sword and not the quarrelsome. Quarrelsomeness and Bravery, I take to be Strangers, and the more bravery I have found in a Man, I have always observed in him the more Unwillingness to quarrel.

We can see here a definite distinction, which was to grow, between acceptance of violent or duelling behaviour as requisite for military men, and the inappropriateness of such violence by gentlemen in civilian life.

There were also advocates for pugilism as a way of satisfying honour with less likelihood of killing or being killed, and there were crazes for pugilistic practice among gentlemen in the latter half of the century. One Comte de Barral, in his Souvenirs de Guerre et de Captivite d’un Page de Napoleon (1812-1815) (pub. 1925), was horrified at the loss of distinction of rank occasioned by the craze when he witnessed a duel in Abergavenny (with thanks to Dr Thurston for the translation):

To give an idea of the love of the English for boxing during this period, a love so strong such as to cause them to forget all difference of social condition, I will cite an occurrence of which I was the witness.

A platoon of cavalry of X regiment was traveling to Monmouth, having spent the night at Abergeveny [Y Fenni/Abergavenny]. The lieutenant in command (one recalls that officers of English cavalry are, in general, from good families), at the point of setting off, the following morning, was getting his men mounted, in front of the inn. A stable hand turned up and asked him, quite impolitely, for the customary tip. The officer refused. Threats from the boy who, without any more manners, suggested that they settled their differences with fisticuffs!

Getting down from his horse, putting down his jacket, throwing his helmet to the right and his sword to the left, this was for our lieutenant immediate business (remember that his troops were still there, on horseback, in fighting order, sword in hand!).

Then, our two champions threw themselves on one another, with great scientific punches. And, when honour was satisfied, their faces in a very bad way, our son of mars straightens himself, silently mounts his pure-blood mare and commands: "By twos!"[2]

But really, the formal practice of duelling by this point was more or less over. The conception of what ‘maketh man’ had, in most quarters, changed radically — swords had been beaten perhaps not into ploughshares, but certainly to stocks-and-shares. The last duel in Scotland took place in 1826; and he last fatal duel in England, that nation of shopkeepers, took place on Priest Hill, between Englefield Green and Old Windsor, on 19 October 1852, between two French political exiles. Duelling was tolerated far longer on the Continent, and as a post-script I would like to end with an example of a duel fought in World War I by two American Foreign Legionnaires who had been transferred to the regular French army:

During a period in the Champagne reserve trenches, Eugene Jacob called Charles Hoffecker a 'dirty boche'. Hoffecker, whose family went to America from the German speaking parts of Switzerland, bitterly resented the epithet, and challenged Jacob to a duel. The challenge was accepted, and the duel came off when the One Hundred and Seventieth went to a village in the rear for periodical repose. Bayonets were the weapons, and the two Americans set to fighting in deadly earnest. Both had taken fencing lessons, and they gave a good display of that art. Hoffecker drew first blood, slightly wounding his opponent in the shoulder; more serious injury might have been done had not the arrival of an officer and a guard of ten men put an end to the fight. It was first proposed to court-martial the two combatants, but when the circumstance bringing about the duel was explained, the Americans were let off with a severe admonition, after they had shaken hands.”

[From Rockwell, American fighters in the Foreign legion, 1914-1918]

Bibliography of secondary sources

Anglin, Jay P. “The Schools of Defense in Elizabethan London.” Renaissance Quarterly 37, no. 3 (1984): 393–410. https://doi.org/10.2307/2860956.

Banks, Stephen. A Polite Exchange of Bullets: The Duel and the English Gentleman, 1750-1850 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2010).

Billacois, François. The Duel: Its Rise and Fall in Early Modern France (New Haven ; London: Yale University Press, 1990).

Leigh, John. Touche: The Duel in Literature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

Manning, Roger B. Swordsmen: The Martial Ethos in the Three Kingdoms (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Peltonen, Markku. The Duel in Early Modern England: Civility, Politeness, and Honour (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Saviolo, Vincentio. A Gentleman’s Guide to Duelling: Vincentio Saviolo’s Of Honour and Honourable Quarrels (Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2013).

Most of the primary sources can be found at the “Library” page of the Linacre School of Defence website.

[1] See the lists of duels in Banks, A Polite Exchange of Bullets.

[2] I am indebted to Dr. Milo Thurston for the English translation of this text.